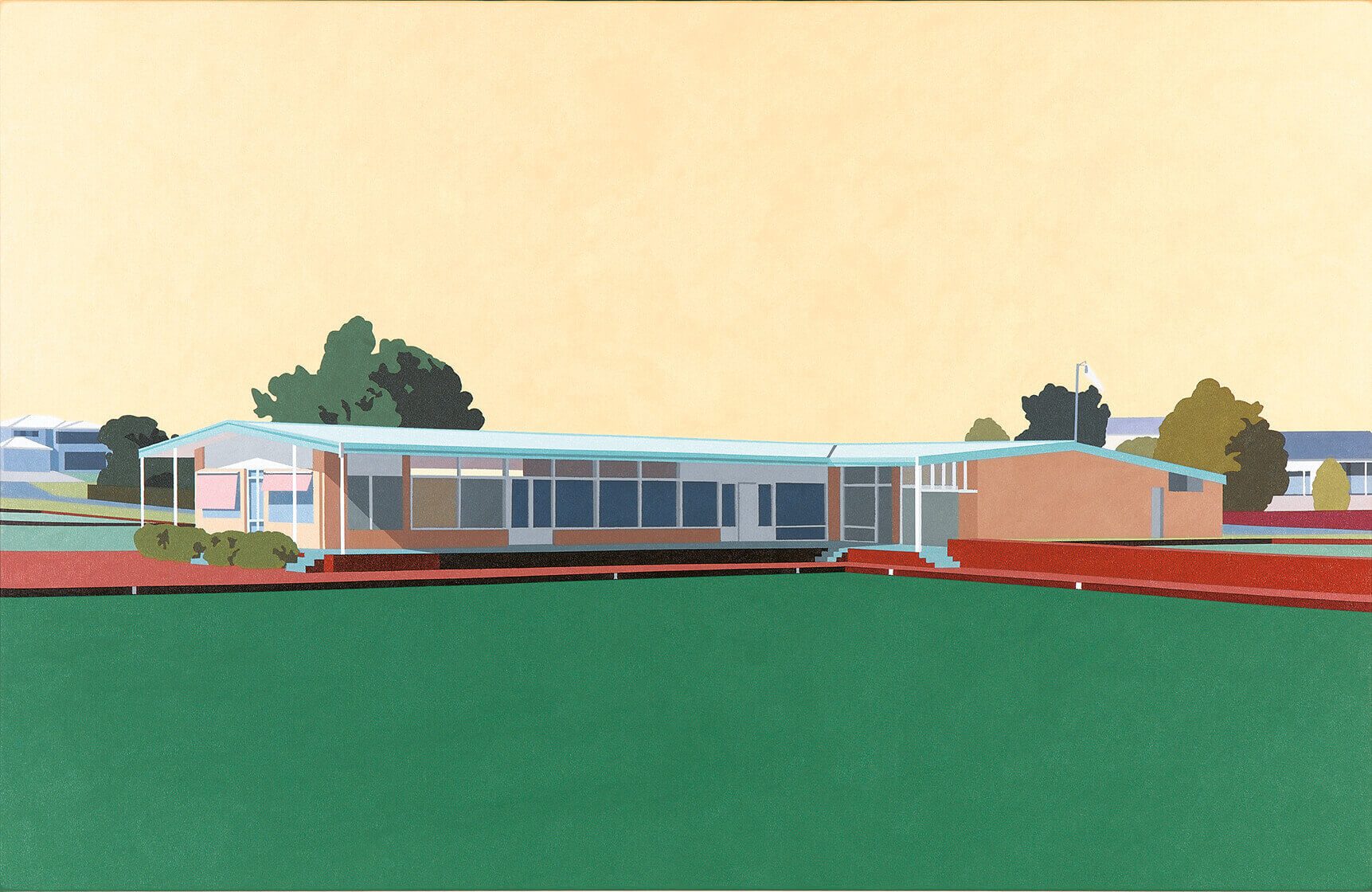

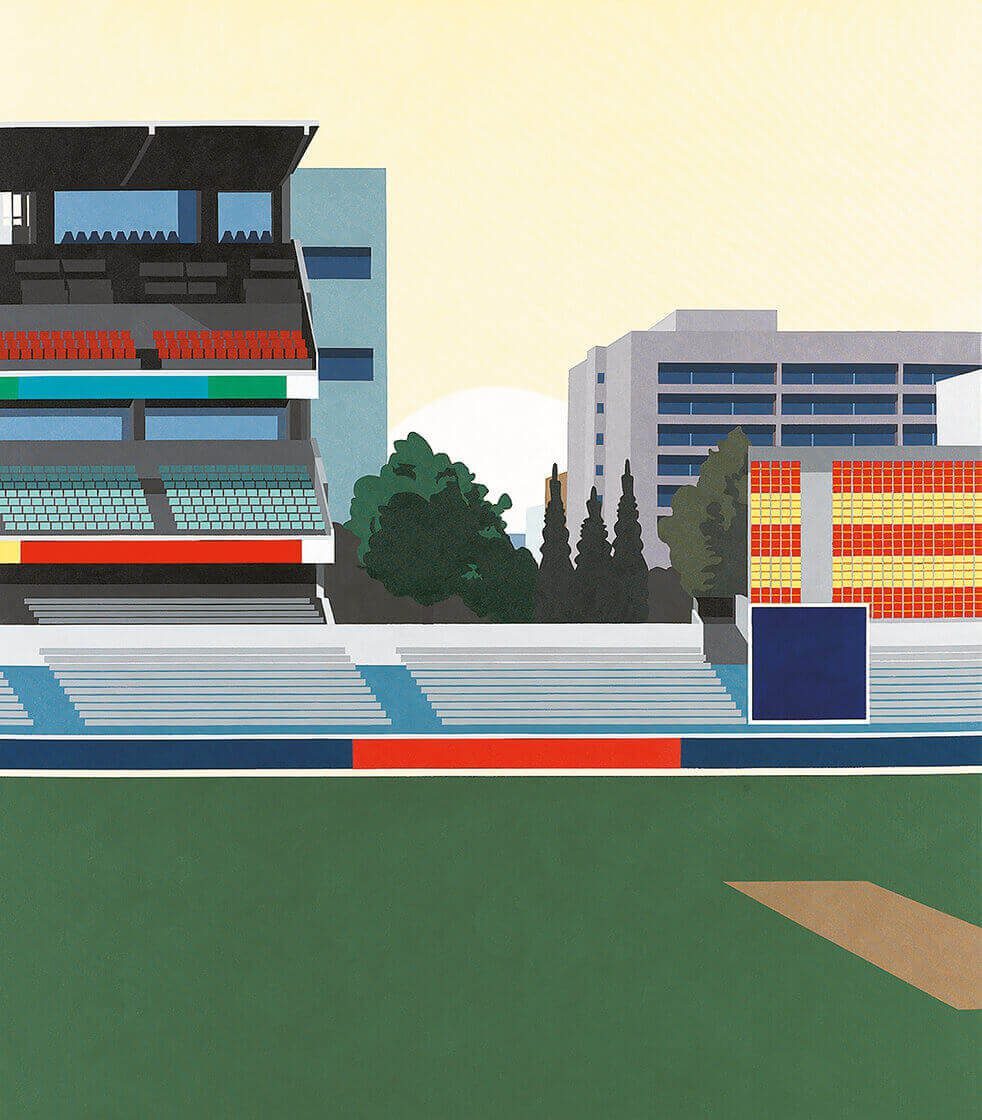

Flatland: A Continuing Romance, September–October 2007, Sullivan + Strumpf

Trance

Robert Cook, August 2007

As L.A. seemed trancelike to Joan Didion in the 1970s [1], so too can Perth. This is due to its sparse, physical characteristics, but also because of the broad emptying aesthetisations of landscape discourse that dominate our experience of the place; the latter acts as a distancing trope between us and life. It is the specific quality of this landscape-trance-effect that Lamb’s work engages with: so instead of ignoring it, instead of wishing it away, Lamb is intent on exploring and revealing its nuances as they exist in Perth, and the Perth in other places. As these dynamics are the outcome of accumulated cultural mediations, it is only natural that Lamb’s works also evolve through a slow process of mediation. Each painting begins as a drawing or photo that is then rendered onto the computer where surplus details from the original scene are gradually culled. What are left are blocks, forms and colours that appear realistic, yet are really the well-worn signs of realism. These are then modulated into various tonal variations. A screen-printing process is used to make the outlines on the canvas and then the acrylic paint is applied. It is an instance of manufacture in miniature, the opposite of urgently jumpy en plein-air impressionism. Instead, Lamb’s works are models of hyper-conscious, distanced reflection. Their crisp, neat finish seems elusively accomplished, having a clean, precise, almost mechanically de-humanised feel. Coolly Warholian in nature, they suggest that the scenes they depict are completely interchangeable. Lamb’s aesthetic flattening in this regard is a key part of the graphic that signifies the global; the smoothing out of details is situated within the bland same-making that argues for pure command over space. In other words, space is tamed through its artificial abstraction that implies it is easily moved over, without the traction of place. The visual sphere Lamb presents, therefore, offers a codified layering that perfectly matches the new world order of endlessly interchangeable non-places. In this, Lamb is neatly commenting on the fact that, since colonisation, this place has always, at least partly, been an “international fantasy”. It has been seen through “other eyes” that have found it so very difficult to see the reality and the quiet, subtle possibilities of what actually exists here. In doing this, Lamb casts the discourse of landscape as it is traditionally known as an entity that, in attempting to represent a very specific set of ideological experiences to the world, actually represents a non-experience; landscape can be obfuscatory as much as revelatory. Here, then, Lamb’s works neither offer empty celebrations of the achievements of modernity, nor the boringly damning critiques of the place that the anti-Perth folk proffer. Instead, they approach a deeper reality, offering a flattened ground upon which to re-think the textured substance of life in a mirage, in a hall of mirrors that is continuingly changing, continually sucked into and out of an internationalising orbit.

Note

[1] Didion, Joan. (1975). “Pacific distances”, in Live and learn (2005). Harper Perennial: London, p. 437.